A Literature Review on Self-care of Chronic Illness Definition Assessment and Related Outcomes

- Protocol

- Open up Admission

- Published:

Health coaching interventions for persons with chronic conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis protocol

Systematic Reviews volume 5, Article number:146 (2016) Cite this article

Abstract

Background

Chronic conditions are increasingly more than common and negatively touch quality of life, disability, morbidity, and mortality. Health coaching has emerged as a possible intervention to assistance individuals with chronic conditions adopt wellness supportive behaviors that improve both quality of life and wellness outcomes.

Methods/design

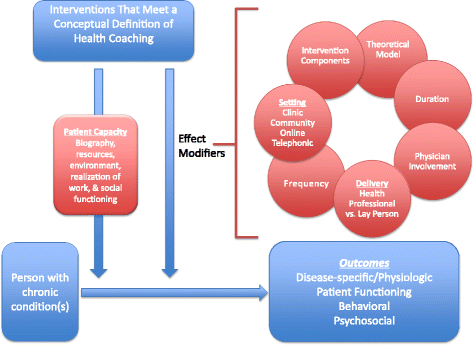

Nosotros planned a systematic review and meta-assay of the gimmicky health coaching literature published in the terminal decade to evaluate the consequence of health coaching on clinically important, disease-specific, functional, and behavioral outcomes. We will include randomized controlled trials or quasi-experimental studies that compared health coaching to alternative interventions or usual care. To enable adoption of constructive interventions, we aim to explore how the event of intervention is modified by the intervention components, delivering personnel (i.e., health professionals vs trained lay or peer persons), dose, frequency, and setting. Assay of intervention outcomes will exist reported and classified using an existing theoretical framework, the Theory of Patient Capacity, to identify the areas of patients' capacity to access and use healthcare and enact self-care where coaching may exist an effective intervention.

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis will identify and synthesize evidence to inform the practice of wellness coaching past providing evidence on components and characteristics of the intervention essential for success in individuals with chronic health conditions.

Systematic review registration

PROSPERO CRD42016039730

Background

Chronic conditions stand for a growing public health problem throughout the earth. In the USA, approximately one-half of adults have one or more chronic condition [1], while 26 % have multiple chronic conditions. Every bit the population ages, multiple chronic conditions volition impact 3 in four Americans 65 and older [2, 3]. Chronic conditions decrease quality of life, increase disability, increment morbidity and mortality, and increment healthcare costs.

Health coaching has emerged equally a widely adopted intervention to aid individuals with chronic weather adopt health supportive behaviors that amend both quality of life and health outcomes. Commonly referred to equally "life coaching," "health coaching," or "wellness coaching," the lack of definitional clarity has made it difficult to written report and compare coaching interventions. The coaching process is viewed as "a systematic procedure and is typically directed at fostering the ongoing self-directed learning and personal growth of the customer" [iv]. A comprehensive conceptual definition of wellness coaching was provided by Wolever et al. who defines coaching as "a patient-centered arroyo wherein patients at least partially decide their goals, employ self-discovery or agile learning processes together with content pedagogy to work toward their goals, and cocky-monitor behaviors to increment accountability, all within the context of an interpersonal relationship with a coach" [5]. There are several features common to nearly all forms of coaching. Commonalities include the core assumption that people take an innate capacity to abound and develop; a focus on constructing solutions; and a focus on goal attainment processes [four].

There is a need for show synthesis to evaluate the effectiveness of health coaching, particularly to examine the components that are necessary for its effectiveness and settings in which information technology is most helpful. Such synthesis can provide evidence of the effectiveness of health coaching that cuts across types and models of coaching. For example, prior to the publication of Wolever et al.'southward conceptual definition, two health coaching systematic reviews made exclusions based on specific labels or narrow definitions of coaching traditions. Kivela et al. explored "life coaching," thereby excluding interventions labeled "wellness coaching," while Ammentorp et al. explored strategies labeled "health coaching" at the expense of excluding interventions labeled "life coaching" or "wellness coaching" [4, 6]. Therefore, we plan to deport a systematic review and meta-assay that further builds on previous systematic reviews by including coaching interventions based on a wide conceptual definition of health coaching [5].

Dissimilar previous syntheses, we too programme to include interventions delivered by lay and peer-coaches. The review past Kivela et al. purposefully excludes coaching interventions non delivered by a health professional [six]. However, Wolever et al. found that approximately six % of coaching interventions used lay coaches while another thirteen % did not provide sufficient data to determine the coaches' background [5]. Therefore, including coaching provided by the growing segment of lay and peer-coaches will provide knowledge almost their application and comparison to health professional-delivered coaching [7–12].

Additionally, the planned review seeks to clarify the characteristics of coaching delivery that go far near constructive by identifying the platonic coaching elapsing, frequency, delivery format, and charabanc qualifications for individuals and subsets of individuals with chronic weather. This information volition assist communities, clinics, health coaches, and healthcare systems to create successful, effective health coaching interventions tailored to the needs of those with chronic conditions.

This review will pay particular attention to the impact of health coaching on outcomes that contribute to patient capacity to access and utilise healthcare and enact self-care. Patient chapters has important implications for wellness outcomes and the feel of care. Individuals experience higher treatment burdens when they have limited capacity to manage emotional bug with family and friends, function and activity limitations, financial challenges, and healthcare delivery inefficiencies [xiii]. Furthermore, patients draw on chapters to make adaptations over time to overcome treatment brunt associated with chronic conditions [xiv]. Studies that have examined capacity have shown that patients nearly disrupted by treatment had serious limitations to their concrete, emotional, and financial capacities [15] while care plans that attended to patient capacity were more than effective in reducing 30-day hospital readmissions [xvi].

Given health coaching'southward potential to meliorate wellness outcomes by supporting and growing patients' capacity to cope with the demands of chronic illness, this review will highlight outcomes related to health coaching'south effect on patient capacity using the descriptive Theory of Patient Capacity. The Theory of Patient Capacity maintains that factors that shape patient chapters include the successful reframing of their Biography, the ability to mobilize new or existing Resource, the support of their Surroundings, their experiential achievement of patient and life Work, and their Social functioning (BREWS) [17]. Coaching as an intervention naturally explores and cultivates human being capacity in each of these areas. Since increasing patient capacity is at present appreciated as a strategy to improve patient health outcomes, we would like to elucidate the relationship between wellness coaching and increasing patient capacity. This human relationship may reveal an opportunity to refine a health coaching approach to focus on Capacity Coaching in patients with chronic conditions and large treatment burdens.

Aim

We aim to explore clinically important outcomes of health coaching interventions for persons with chronic atmospheric condition applying a broad conceptual definition of health coaching and including peer and lay-wellness coaching interventions. Comparators volition include usual care, therapy interventions, health teaching, and support groups.

Important outcomes for patients' health will include disease-specific and physiologic outcomes, behavioral and psychological outcomes, and measures of patient performance (ADLs). All outcomes that play a role in patients' capacity, as described past Theory of Patient Capacity, volition be categorized using the BREWS framework.

This review further aims to identify the characteristics of coaching commitment that make information technology most effective for individuals with chronic conditions by identifying the platonic coaching elapsing, frequency, commitment format and coach qualifications, involvement of the master care provider, for individuals or subsets of individuals with chronic weather.

Methods

Study design

Nosotros volition conduct a systematic review and meta-assay that adheres to the reporting guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [xviii]. We have developed this protocol in accordance with the PRISMA-P statement, which is included as an boosted file (Additional file 1) [19].

Study eligibility

Types of studies

Nosotros volition include studies published in English, which utilise a randomized controlled trial or quasi-experimental blueprint to compare health coaching to standard care or other culling interventions.

Types of participants

We will include studies that seek to use coaching as an intervention for adults aged 18 and older with one or more than chronic conditions. We volition utilise the Agency for Healthcare Quality and Enquiry's (AHRQ) definition of a chronic condition as i "lasting 12 months or more and limiting self-intendance, independent living, or requires ongoing medical intervention" [20]. Coaching interventions that are delivered in a healthcare setting but participants do not accept a chronic condition will exist excluded. For example, coaching services could be provided to patients receiving principal care at a health clinic, who are otherwise healthy, for general health maintenance, stress direction, etc.

Types of interventions

We volition include studies that use coaching interventions for individuals with chronic conditions. These interventions may be delivered in-person, by telephone, by internet, or a combination of multiple delivery methods. The interventions may be delivered individually to patients, equally part of a group, or a combination. We will seek as much data near the intervention from the papers retrieved to make up one's mind if information technology meets definition of coaching presented by Wolever et al. for inclusion [five]. Specifically, in social club to meet inclusion under this definition, interventions must (1) be patient-centered in that patients must at least partially determine their goals; (2) use self-discovery or active learning processes together with content education to work toward patient goals; (iii) have a component of behavioral self-monitoring to increase accountability; and (4) pursue these activities in the context of an interpersonal relationship with a coach [5]. Finally, while Wolever et al. specifies that wellness professionals use these strategies, we are interested in the delivery of coaching interventions by health professionals also every bit those that are outside traditional healthcare roles, which may include customs health workers or peer-coaches, which, as indicated above take become increasingly common in the recent literature.

Types of comparators

We will include studies that compare coaching to standard clinical care or alternative intervention(southward). Alternative interventions to which coaching may be compared may include merely are non limited to patient education interventions, counseling, support groups, or chronic affliction self-direction courses. These interventions may have individual components included in the Wolever definition of coaching but exercise not satisfy all four criteria. For example, patient education interventions may include content education in the context of an interpersonal human relationship simply not include any cocky-discovery or goal-setting.

Types of effect measures

We will extract 3 types of outcomes: (1) illness-specific (preferably patient important outcomes although surrogate outcomes are more than likely be pursued in health coaching trials), (two) outcomes that relate to patient performance and quality of life such as the ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs), and (3) behavioral and psychosocial outcomes.

Some of these outcomes will be disease-specific and some will be common across diseases, particularly those that chronicle to function and quality of life. Because we are interested in coaching as a mechanism to amend patient capacity, where feasible we will categorize outcomes using the Theory of Patient Capacity every bit a guide into outcomes that shape related to patient reframing of their Biography (i.eastward., office office, quality of life), the ability to mobilize new or existing Resources (i.due east., physical function, activity limitation), the back up of their Environment (i.eastward., healthcare team support), their experiential accomplishment of patient and life Work (i.east., self-efficacy, patient activation), and their Social performance (i.eastward., social back up) [17].

Search strategy

Two expert reference librarians (LP, PJE) will create and conduct the initial search of relevant search databases including Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE, CINAHL, Ovid PsycINFO, Ovid Cochrane CENTRAL, and Scopus. This search volition include studies from February 2006 to February 2016 that include key terms such as passenger vehicle, health, wellness promotion, health behavior, lifestyle, peer, recover and chronic disease, as well as disease-specific search terms that we have used in previous reviews [17] for a more than sensitive search of all chronic weather. Nosotros will review the references of included studies to ensure that no additional studies should be included. A total search strategy is included equally an appendix to this protocol (Additional file ii).

Pick of studies

Duplicates are removed past the librarians (LP, PJE), using EndNote'due south duplicate identification strategy then manually. When reviewing and retrieving citations, whatever missing citation data is located, or added manually. Afterwards removing duplicates, we will import retained studies into systematic review software (DistillerSR, Ottawa, ON, Canada). We will screen studies in 2 phases: abstract screening and full-text screening. In each stage, iii authors (KB, SB, and SA) will undergo training to ensure clarity about study purpose, inclusion, and exclusion criteria and then screen a subset of abstracts in triplicate to ensure practiced inter-rater agreement. After this step, in both phases, each abstruse or total text will be screened individually and in indistinguishable by ii of the trained reviewers. In the abstruse screening phase, both reviewers must be in understanding in order to exclude an commodity; conflicts will be included. During full-text screening, conflicts will be resolved past consensus. If consensus cannot be achieved between the two reviewers, the 3rd reviewer will intervene.

Data extraction

Data volition be extracted using the aforementioned systematic review software used for abstruse and full-text screening (DistillerSR, Ottawa, ON, Canada). We accept adult and airplane pilot tested the extraction class to ensure constructive and efficient data extraction. Information extraction volition be performed in duplicate. Paired reviewers will review data extraction conflicts by reviewing studies to correct errors. Any extraction conflicts not hands resolved by re-review of the full text volition exist resolved by consensus. We volition extract atomic number 82 author names, engagement, state in which the study was conducted, chronic condition(s) targeted, study aim, study blueprint, sample subjects characteristics including full number, age, sexual practice, loss to follow-up, ethnicity/race, sample income information, intervention and command characteristics including the person delivering the intervention, number of sessions prescribed, elapsing of session prescribed (minutes), mean number of sessions (actual), hateful duration of sessions (actual), length of intervention (actual, in weeks), coaching/theoretical model(s), setting, description of the coaching (goal-setting, relationship with motorcoach, etc),whether it is a multi-component intervention, whether a clinician was involved in the intervention, and control grouping characteristics. We will note all outcome measures related to the patient's health or their chapters to access and utilise healthcare and enact cocky-care, when each upshot measure was nerveless during the written report, measures used to collect outcomes, and main findings. These include, but are not limited to, outcomes such as quality of life, global health condition, activity limitation, pain, depression, anxiety, HbA1c, body mass alphabetize (BMI), self-efficacy, patient activation, physical activity, social support, and mental health.

Risk of bias cess

We will assess risk of bias using the Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias, which prompts assessment in the post-obit areas: randomization, quality of randomization (any important imbalances at baseline), allocation concealment, level(s) of blinding, incomplete outcome data (due to attrition or otherwise), selective reporting, and other sources of bias, considering other factors such as conducting intention to treat analysis and the office of funding in the study [21]. Nosotros will include a study-level table that describes the gamble of bias in these categories for each study and describe the chance of bias in the overall body of evidence. No studies volition be excluded based on the run a risk of bias assessment.

Statistical analysis

As a general framework, we plan to bear meta-analysis using a random-effects model. We chose this model a priori to contain within-study and between-study heterogeneity since we anticipate divergence beyond studies population and interventions. If the number of studies in a detail analysis is large (15–xx), we will utilize the DerSimonian Laird method [22]; if the number is smaller, we will use the Knapp–Hartung small-sample estimator approach method [23]. We will evaluate heterogeneity using the I 2 statistic, τ 2, and the Cochrane Q statistic. Substantial heterogeneity will be divers as I 2 larger than 50 % or Q test with a p value <0.ten. It is probable that certain outcomes will exist measured using unlike scales or various definitions and would require standardization. In this instance, we would estimate the standardized effect size and present the effect of wellness coaching in standard deviation units. If we take more 20 studies per analysis, we will construct funnel plots and test their symmetry using one of the several available techniques that test for small study event (east.thousand., Egger'south regression). Unfortunately, all these methods have serious limitations [24].

Exploring heterogeneity

Since wellness coaching is a circuitous intervention by nature, we volition follow suggestions on synthesizing show from circuitous interventions [25]. Briefly, such framework emphasizes that prove users are more interested in knowing when the intervention works (delivered by whom and how and how often, and in which setting and patient subgroup). Such knowledge is more important than the simple question of "does it work?" Therefore, we plan to conduct univariate and multivariate meta-regression to explore the consequence of such characteristics (the independent variables) on the consequence size (the dependent variable). This exploration of heterogeneity may help in identifying factors, components, and conditions in which wellness coaching is more than effective and, therefore, may facilitate implementation of such effective components of the intervention. Other key characteristics of the population and setting (e.k., diabetes) volition also exist explored as possible covariates. Analyses volition exist performed in Stata, version 13 (StataCorp). Using the (Metareg) command, the event size will be the dependent variable and the circuitous intervention characteristics will exist the contained variables. The statistics obtained from the random permutations can exist used to accommodate for such multiple testing past comparison the observed t-statistic for every covariate with the largest t-statistic for any covariate in each random permutation. We volition produce a bubble graph showing the fitted regression line [26]. We will perform a quantitative assay when possible (i.e., when we look that studies have similar population, intervention, comparator and outcomes; to the extent that a similar effect size is anticipated if studies were pooled). We volition pursue a narrative analysis when statistical assay is not an option.

Quality of evidence

We will evaluate quality of evidence (certainty of evidence) using the GRADE arroyo [27]. Quality of evidence from randomized trials starts at high and can be rated downwards for methodological limitation, imprecision, indirectness, inconsistency, or publication bias. Quasi-experimental studies may start at low if they were conspicuously nonrandomized [28].

Discussion

Chronic conditions are the leading causes of morbidity and bloodshed in the USA and beyond the globe. A new public wellness arroyo requires efforts in the realms of public health policy, customs based programs, and clinical preventive services [29]. Based on a growing trunk of evidence that health coaching tin can improve health outcomes for individuals with chronic weather, health coaching as an individual or group intervention may support public health efforts in the realms of community-based programs and clinical preventive services [4, 6].

While previous reviews have captured the effects of wellness coaching on diverse health outcomes, we hope to substantiate this work with a more inclusive approach that includes all coaching interventions and the growing trunk of work performed past peer and lay coaches. While the strength of this review is its considerable depth of data and broad inclusion criteria, its potential limitations must be considered. Nosotros wait that there may be limitations to the evidence summary and synthesis, related to poor indexing of the coaching literature and lack of reporting of the characteristics of interventions, to the extent that meta-regression may not be feasible. Caution in the interpretation of meta-regression is needed since misleading associations can be observed due to ecological bias and confounding. Lastly, operationalization of the "BREWS" framework will be iterative during the acquit of this review since this arroyo is novel and therefore analysis methods would exist exploratory.

Finally, our novel sub-focus on the relationship between health coaching and patient capacity will elucidate any basis to the hypothesis that nosotros can heighten wellness in chronic atmospheric condition by focusing on developing a sub-category of coaching, accounted "Capacity Coaching." This is in line with the extensive trunk of enquiry growing to support the practice of Minimally Confusing Medicine [xiii–15, xxx–32], of which Capacity Coaching would be a component. Finally, to make it easier to design and implement effective health coaching interventions in support of the 66 % of Americans with chronic atmospheric condition, this review seeks to identify key characteristics of successful coaching interventions. In addition to informing coaching practice broadly, Chapters Coaching will incorporate the knowledge gained from this review with its theoretical underpinnings, to better inform its model with ideal format, timing, grooming, and delivery personnel (Fig. 1).

Health coaching analytic framework

Overall this review volition support clinicians, nurses, clinics, healthcare systems, wellness plans, community health organizations and public health departments every bit they consider scalable health coaching interventions for individuals with chronic conditions. Every bit we gain insights about the elements of effective health coaching interventions that optimally increase patient capacity to self manage chronic conditions, we strengthen the medicine-public health partnership needed to manage and reverse the chronic disease trend.

Abbreviations

- ADLs:

-

Activities of daily living

- AHRQ:

-

Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research

- BMI:

-

Body mass alphabetize

- BREWS:

-

Biography, resources, environment, work, and social functioning

References

-

Chronic Diseases and Health Prevention. Chronic Diseases: The Leading Causes of Death and Disability in the The states. http://www.cdc.gov/chronicdisease/overview/ Accessed 29 Aug 2014.

-

Anderson GF. Chronic care: making the case for ongoing care. Princeton: Robert Forest Johnson Foundation; 2010.

-

Barnett 1000, Mercer SW, Norbury M, Watt One thousand, Wyke S, Guthrie B. Epidemiology of multimorbidity and implications for health care, research, and medical education: a cross-sectional written report. Lancet. 2012;380(9836):37–43.

-

Ammentorp J, Uhrenfeldt L, Affections F, Ehrensvard M, Carlsen EB, Kofoed PE. Can life coaching meliorate health outcomes? A systematic review of intervention studies. BMC Health Serv Res. 2013;13:428.

-

Wolever RQ, Simmons LA, Sforzo GA, Dill D, Kaye Grand, Bechard EM, et al. A systematic review of the literature on health and wellness coaching: defining a Key behavioral intervention in healthcare. Glob Adv Health Med. 2013;2(iv):38–57.

-

Kivela K, Elo S, Kyngas H, Kaariainen M. The furnishings of health coaching on adult patients with chronic diseases: a systematic review. Patient Educ Couns. 2014;97(ii):147–57.

-

Goldman ML, Ghorob A, Hessler D, Yamamoto R, Thom DH, Bodenheimer T. Are Low-income peer health coaches able to master and utilize evidence-based health coaching? Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(one):36–41.

-

Knox L, Huff J, Graham D, Henry M, Bracho A, Henderson C, et al. What peer mentoring adds to already good patient care: implementing the carpeta roja peer mentoring programme in a well-resourced health care system. Ann Fam Med. 2015;xiii(1):59–65.

-

Safford MM, Andreae S, Cherrington AL, Martin MY, Halanych J, Lewis M, et al. Peer coaches to improve diabetes outcomes in rural Alabama: a cluster randomized trial. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(1):18–26.

-

Tang TS, Funnell MM, Sinco B, Spencer MS, Heisler G. Peer-led, empowerment-based arroyo to self-management efforts in diabetes (PLEASED): a randomized controlled trial in an African American community. Ann Fam Med. 2015;xiii(1):27–35.

-

Yin J, Wong R, Au Southward, Chung H, Lau Chiliad, Lin L, et al. Furnishings of providing peer back up on diabetes management in people with type 2 diabetes. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(1):42–9.

-

Zhong X, Wang Z, Fisher EB, Tanasugarn C. Peer back up for diabetes management in primary care and community settings in Anhui Province, Red china. Ann Fam Med. 2015;thirteen(1):fifty–8.

-

Eton DT, Ramalho de Oliveira D, Egginton JS, Ridgeway JL, Odell L, May CR, et al. Building a measurement framework of burden of treatment in complex patients with chronic conditions: a qualitative study. Patient Relat Upshot Meas. 2012;iii:39–49.

-

Ridgeway JL, Egginton JS, Tiedje K, Linzer G, Boehm D, Poplau S, et al. Factors that lessen the burden of treatment in complex patients with chronic atmospheric condition: a qualitative study. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2014;8:339–51.

-

Boehmer KR, Shippee ND, Beebe TJ, Montori VM. Pursuing minimally confusing medicine: disruption from illness and health care-related demands is correlated with patient capacity. J Clin Epidemiol. 2016;74:227–36.

-

Leppin AL, Gionfriddo MR, Kessler One thousand, Brito JP, Mair FS, Gallacher K, et al. Preventing thirty-day hospital readmissions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(7):1095–107.

-

Boehmer KR, Gionfriddo MR, Rodriguez-Gutierrez R, Abu Dabrh AM, Leppin AL, Hargraves I, May CR, Shippee ND, Castaneda-Guarderas A, Zeballos Palacios C, Bora P, Erwin PJ, Montori VM. Patient Capacity and Constraints in the Feel of Chronic Disease: A Qualitative Systematic Review and Thematic Synthesis. BMC Family Practice. 2016. In press.

-

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses: the PRISMA argument. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(x):1006–12.

-

Moher D, Shamseer L, Clarke M, Ghersi D, Liberati A, Petticrew G, Shekelle P, Stewart LA. Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-assay protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Syst Rev. 2015;4(1):ane.

-

Agency for Healthcare Quality and Inquiry. AHRQ Announces the Release of the Chronic Conditions Indicator (CCI) for financial year 2012 (November 2011). http://world wide web.hcup-united states.ahrq.gov/news/announcements/CCI_1111.jsp. Accessed 24 Apr 2014.

-

Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Juni P, Moher D, Oxman AD, et al. The Cochrane Collaboration's tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928.

-

DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7(3):177–88.

-

Cornell JE, Mulrow CD, Localio R, Stack CB, Meibohm AR, Guallar Eastward, et al. Random-effects meta-analysis of inconsistent furnishings: a fourth dimension for change. Ann Intern Med. 2014;160(4):267–70.

-

Lau J, Ioannidis JP, Terrin N, Schmid CH, Olkin I. The instance of the misleading funnel plot. BMJ. 2006;333(7568):597–600.

-

Petticrew K, Anderson L, Elderberry R, Grimshaw J, Hopkins D, Hahn R, et al. Complex interventions and their implications for systematic reviews: a pragmatic approach. J Clin Epidemiol. 2013;66(eleven):1209–14.

-

Harbord RM, Higgins JP. Meta-regression in stata. Meta. 2008;8(iv):493–519.

-

Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Brozek J, Alonso-Coello P, Rind D, et al. GRADE guidelines half-dozen. Rating the quality of evidence—imprecision. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(12):1283–93.

-

Murad MH, Montori VM, Ioannidis JP, Jaeschke R, Devereaux PJ, Prasad Thou, et al. How to read a systematic review and meta-analysis and utilize the results to patient care: users' guides to the medical literature. JAMA. 2014;312(2):171–9.

-

Halpin HA, Morales-Suarez-Varela MM, Martin-Moreno JM. Chronic affliction prevention and the new public health. Public Health Rev. 2010;32(1):120–54.

-

May C, Montori VM, Mair FS. We need minimally confusing medicine. BMJ. 2009;339:b2803.

-

Gallacher K, May CR, Montori VM, Mair FS. Understanding patients' experiences of treatment brunt in chronic heart failure using normalization process theory. Ann Fam Med. 2011;9(3):235–43.

-

Gallacher One thousand, Morrison D, Jani B, Macdonald Due south, May CR, Montori VM, et al. Uncovering treatment brunt every bit a key concept for stroke care: a systematic review of qualitative research. PLoS Med. 2013;x(6):e1001473.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Jean F. Wyman, PhD, Professor and Cora Meidl Siehl Chair in Nursing Research of the University of Minnesota School of Nursing for her contributions in the early conceptual phase of this manuscript.

Funding

No grant back up was provided for this project. All support for publication was provided through Mayo Clinic internal funding.

Availability of data and materials

Data can exist obtained by contacting the corresponding author of the last manuscript.

Authors' contributions

KB, SB, and SA conceptualized the research question and report pattern with communication of MHM. The search strategy was adult in collaboration with LP and PJE. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Authors' data

Not Applicative.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they take no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Not Applicative.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not Applicable.

Author information

Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional files

Additional file one:

PRISMA-P checklist acknowledges we accept met key reporting items for Systematic review and Meta-Analysis Protocols. (Doc 84 kb)

Boosted file 2:

Literature search strategies. Includes total search strategies used in the systematic review. (DOCX 34 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open up Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution iv.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/iv.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you requite advisable credit to the original author(south) and the source, provide a link to the Artistic Eatables license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zippo/1.0/) applies to the information made bachelor in this commodity, unless otherwise stated.

Reprints and Permissions

Near this article

Cite this article

Boehmer, K.R., Barakat, S., Ahn, South. et al. Health coaching interventions for persons with chronic conditions: a systematic review and meta-assay protocol. Syst Rev 5, 146 (2016). https://doi.org/ten.1186/s13643-016-0316-3

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0316-3

Keywords

- Wellness coaching

- Wellness coaching

- Life coaching

- Chronic disease

- Chronic condition

- Patient capacity

wisewouldarresplet.blogspot.com

Source: https://systematicreviewsjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s13643-016-0316-3